I actually wrote the following article several months ago. I've been dithering on whether to post it or not, as it has the potential for kicking off a wave of negativism about cameras, as well as the usual hate mail I tend to get when I'm being provocative.

But I keep getting the same basic questions coming into my In Box, and this article answers those, so I've decided to go ahead and publish. Please note that this is my long-term prediction, not reality. On the other hand, I did call the top of the market ten years before it happened, and within a six month window of the actual date and within 10% of the actual maximum number shipped. But note my comment about it being easier to predict tops than bottoms.

The camera market is in continuous decline now, pretty much everywhere except in the average mirrorless camera price, which has been going up due to so many full frame and high-end cameras being introduced.

So the operative questions are: is there going to be a market bottom, and what will be that bottom?

That's not as easy a projection as it sounds. I've always found that projecting market tops within a reasonable +/- is far easier than market bottoms. That's because market tops tend to follow well-established patterns. The slope of the highest growth cycle coupled with a projection of per household adoption tends to give you a very good idea where the top is. (Okay, the math is a little more complex than that, but the point is the same: you're using some known data points, which have tended to do well in predicting market tops.)

Market bottoms, however, are much more difficult to predict, as often there's disruption—technological and/or economic—that comes into play, plus a market may not absolutely die. Add in demographic factors, how fast the big players transition or respond to market trends and other technology, plus more, and you have a lot of variables in play, and many of them are contradictory.

Records (LPs) were projected by many to die. They're analog and awkward in size, expensive and difficult to produce, plus necessary suppliers were cut to the minimum. For awhile, the thing you needed to play them couldn't be found to be purchased new in many markets. And yet, here we are in 2019 and LP sales are growing and may actually rise above the rapidly-declining CD sales this year. That's not really because LPs are doing so well, it's that they found their market bottom and then started to build a modest growth from there. CDs, unfortunately, will likely die off, as if you want digital and convenient, streaming just works better. And frankly, having no physical product is less expensive for everyone when the product is digital.

In the interchangeable lens camera world, we have film SLR, DSLR, and mirrorless to think about. Film SLRs have absolutely hit bottom, and it's a very low bottom of less than 10k new units/year. That's not enough to sustain an industry, though it might be enough to sustain a very small piece of a larger company. Growth seems unlikely for film SLRs, though so does death. Which is probably why the Nikon F6 is still available new. Also: film SLRs are dependent upon film continuing to be produced, so the camera makers aren't in charge of their own destiny here.

In projecting a market bottom for DSLR/mirrorless cameras, you need to predict several things:

- Size of overall market

- Distribution of sensor size

- Distribution of market share

Obviously, the last two derive from the first, so let's tackle overall market size first.

ILC shipments went 20.2m, 17.1m, 13.8m, 13m, 11.6m, 11.7m, 10.7m from 2012 to 2018, and 2019 is looking like it could be as low as 8m (though likely closer to 9m). That's units being produced by the Japanese camera companies, and as you might have noticed from the build-up of inventories at dealers, the camera companies are probably being optimistic as to what the actual market size currently is. You can manipulate that some with extra sales and marketing efforts, but eventually the "keep last generation on market at lower price while introducing new models" strategy tends to produce worse and worse results.

Most forecasts I've seen project a 10% average decline (in units or value) through the foreseeable future. I think unit collapse will probably go higher than that. The reason is simple: camera companies have not proven that they can bring new buyers into the ILC market. Existing buyers are mostly an aging population that's diminishing in size, and those folk are not updating as frequently as they used to.

I'm going to put a stake in the ground and predict ILC volume will be 4m units in 2023. It's possible that isn't the bottom, that we go all the way down to 3m units. It's possible that 2023 isn't the bottom year. However, market size is such an existential problem at Canon, Nikon, and Sony that they're going to have to find a way to keep the market from slipping below 4m units. That means that they have to embrace the 21st century with their products and start attracting younger users again. I believe that's possible, but I also don't see clear signs that any camera company has figured this out. (Sure, the average buying age of a Sony purchaser is lower than that of the average Nikon purchaser at this point, but that age is still in the Gen X/Boomer realm. They're not making any more of those models ;~).

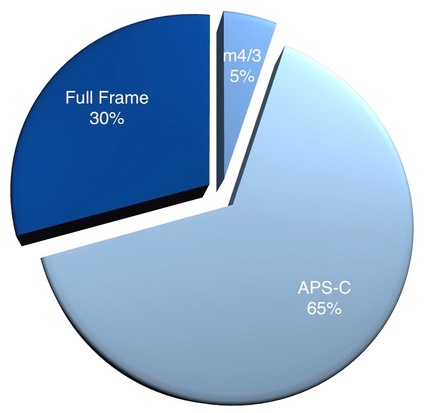

Okay, next, what sensor size is going to be in those 4m cameras? Here's my "best case" scenario:

That's right, APS-C doesn't go away (m4/3 might if it can't find a way to swim to a protected area of the pond in the market size contraction; the GH-5 sort of does that, but what else does?). Thing is, if there's going to be 4m buyers at bottom, most of those are still going to be spending <US$1000.

Though full frame sensors are getting easier and cheaper to produce, I've written since the beginning of digital that there's enough cost benefit to smaller sensor sizes that they will continue to have a place in the market. Remember, every US$50 in manufacturing cost is US$175 implied in consumer price. APS-C gets cost benefits at the sensor and shutter, for sure, but by making additional reductions (lower quality EVF, etc.) US$50 savings or higher are more than possible.

Indeed, the difference between a US$1300 Canon RP and a US$900 Sony A6400 body can mostly be explained by manufacturing costs, despite Canon's sensor re-use. Moreover, from a consumer point of view a price point below US$1000 is very different than any price point above it. Realistically, a lot of the entry camera volume is currently in the US$400-700 range, a range that full frame simply can't get down to. I don't see that changing.

But there's another factor here: maintaining profit. As market volume contracts, all of the Japanese camera companies want to sell more expensive cameras. That's the way they believe they'll survive. Thus, if one maker really wants to go all full frame and get down below that US$1000 price point, they'd be doing the opposite: giving up profit for volume. But there's nothing that says that volume would go up. So what they'd really be doing is giving up profit.

Thus, I'm forecasting that, at bottom, most of the market is still APS-C. If it isn't, the bottom is going to be far, far lower, because full frame's costs will keep it from dropping below a certain price point to maintain profit, and therefore won't expand volume.

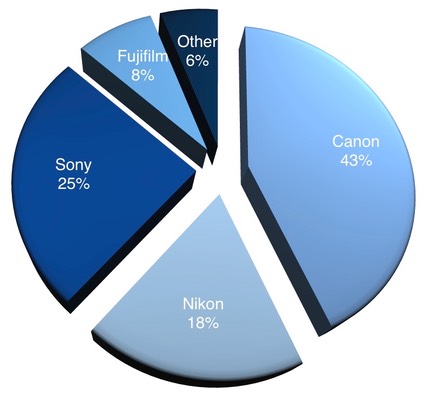

Next, there's the issue of who is making those 4m units.

I see Canon and Nikon getting weaker than their strongest market shares in ILC to date, with Fujifilm and Sony getting stronger. That will, in essence, swap the Nikon and Sony positions. Thus, two of the top three supplier positions will be lower than their max in my prediction (historically Canon hit 51% max, Nikon hit 38% max, Sony hit 18% max; since that adds up to more than 100%, something has to give ;~).

I don't think Canon can hold 50% of the market as they seem to think they can. Not without lowering their gross product margins (GPM) to the point where it would impact their stock price. I think that Canon will find that they can hold a 40%+ share, but they'll have to back off from tying to completely tie up the market. All that chaff they have in the APS-C DSLR side has to be completely re-rationalized to get the GPM back up. And the initial lower-end foray in the full frame mirrorless isn't going as well as they hoped. Canon is going to lose market share soon, the only question is how much.

Nikon apparently decided several years ago to stop trying to hold onto market share, but to rationalize their product line and focus on higher GPM at lower volumes. We're still in the early stages of that change in strategy. I think they might slide all the way down to 16% ILC market share before getting back up to something approaching their current position. They just don't seem to have the product stream coming that would keep them from sliding some. But that also seems to be by design. Here's what to watch: does Nikon Imaging's GPM bottom out and start to recover? If so, their plan is working and I'm pretty sure they'll hold a substantive chunk of the market and stay in the Big Three.

Sony, of course, is the winner in my predictions. At their worst point, they may have slid down to 12% market share, but 14-18% is a realm they've spent a lot of time in. That's begun to change as Alpha mirrorless has matured into a full product line from consumer APS-C to full frame to professional video. Sony has the advantage of being earliest mover—and by quite a few years—to a one-mount, all mirrorless strategy, and that should pay off for them as we head to market bottom.

A lot of you might not remember this, but a bit over a decade ago I wrote that Nikon and Sony had formed an unseen and informal alliance behind the scenes. The goal of that alliance was supposedly to take market leadership away from Canon. Take a close look at the market shares I predict in the above chart: Canon 43%, Nikon/Sony 43%. That was exactly what I was referring to: the combined partnership beginning to erode Canon's dominance.

My observation (based on conversations with several Nikon/Sony executives) back in 2006 was this: Nikon's sensor expertise was melding even more with Sony's. Note that the Nikon-designed D2x sensor showed up in both Nikon and Sony cameras, and really kicked off the transition at Sony Semiconductor from CCD to CMOS for large sensor cameras. Nikon since then appears to have been at minimum a pollinator and at maximum an originator/backer of quite a few technologies we take for granted with Exmor now: column ADC, dual-gain, and on-sensor phase detect.

At the time, I think that Nikon thought that the ideal result of such an informal relationship was going to be Nikon #1 in market share, with Sony fighting with Canon for #2. But at the time, the Imaging executives were in control of Nikon, not the current Precision and banking industry leadership, who seem much more leery of true consumer products. I believe in 2016 the changeover in Nikon's top management decided upon a different outcome: not worry about market share as long as the prosumer/pro market could be retained profitably and that the Nikon/Sony "partnership" could eventually unseat Canon's dominance.

There's a word that is used often in Silicon Valley that describes what Nikon and Sony have been doing: coopetition. Note that Canon is for the most part a loner: their dominance has allowed them to not have to really share research and technology exploration, and to develop everything from sensor to camera themselves. In this respect they are much like a company such as GM or Ford used to be in the auto industry (these days, almost everyone is in coopetition relationships in the auto industry and no longer going it alone).

The dirty little secret is that Nikon has always valued outside research as much as their own, they just didn't often trumpet or admit their adoption of it. About the closest they ever did to that was to say that they'll always choose the best sensor technology for each camera, regardless of origin. Sony Semiconductor, meanwhile, has turned into the dominate force they are by licensing, purchasing, and adopting technologies from everywhere. Yes, a number of their technologies are home grown, but you'd be surprised at how many aren't.

Thus, a Nikon/Sony coopetition arrangement is somewhat natural for both companies. Moreover, here's something that doesn't get talked about much: Add up the top 10 intertwined shareholders for each and you get: 24% of Nikon's shares and 23% of Sony's shares accounted for (you also get 17% of Canon's stock accounted for that way, too). There's strong overlap in shareholder interest in seeing Nikon and Sony coopepeting.

Okay, that's my basic prediction of market bottom. It might happen in late 2021, or 2022, or 2023. Come back in four years to see if I'm right.