News/Views

Hindsight is...

One interesting matter for historians to consider will be how Nikon handled the film SLR to DSLR transition versus how they handled the DSLR to mirrorless transition. In both cases, insightful forward-thinkers were clearly able to see that transitions were necessary and inevitable. In the case of the end of film, the user benefits of DSLRs were immediate results, no (obvious) on-going supply and processing costs, and at higher examination levels things like finally having a guaranteed "flat" focal plane (film tended to crinkle or bend). With mirrorless the obvious user benefits were previewed results, fewer parts and complications, somewhat smaller size and weight.

From the manufacturer's viewpoint, the transition from film to DSLR was actually not particularly to their benefit. The only real simplification for them was losing the transport of the film within the camera, but that came at the expense of extraordinary complications in terms of sourcing and dealing with things they didn't need to deal with before (like coming up with an image sensor and all the things that implied in the camera). By contrast, the transition from DSLR to mirrorless was highly in favor of the manufacturers, as it reduced parts count, simplified manufacturing and alignment issues, and allowed for differentiation.

Here's how I looked at it in simplified form:

In both transitions, customers get benefits, but that comes with cost, complexity, and re-learning issues. In the film-to-DSLR transition the odds were stacked against the camera makers, but in the DSLR-to-mirrorless one, there was literally no friction for them to move to mirrorless, just lots of benefits.

So, given the above, why was Nikon the first to fully attempt a transition to DSLR but last to move to mirrorless?

Simply put, it's due to top management decision making, and one that is fraught with self-examination angst. Nikon was down to a 25% market share in the 90's with film SLRs, with Canon completely dominating the market with at least double the share. Nikon's pride was hurt. Having entered the camera market prior to Canon and having had initial success with the F bodies, now they were a very distant second. The whole autofocus fiasco—Nikon being asleep at the wheel let Minolta suddenly push Nikon down to the #3 position, at least for awhile—didn't help matters. If Nikon thought that DSLRs were the future—and it was clear to many of us even in the early 90's that they were—they decided that they could pull a Minolta and get there first, and thus upset the market balance in Nikon's favor.

Which is exactly what happened. Even once Canon fully responded, the market had been reset with Canon in the 40-45% share range typically, and Nikon in the 30-35% share range typically. Indeed, in some particular categories of camera, Nikon tended to be first at times (especially true once full frame appeared at Nikon with the D3).

The question, of course, is if being first to transition worked once for Minolta (autofocus), once for Nikon (DSLR), why is it that when there was an obvious next transition—remember, I started writing about mirrorless in 2008 and started sansmirror.com shortly thereafter—that Nikon was the last to transition?

That's a good question for future researchers and scholars to answer. Nikon did attempt mirrorless in 2011, using some of their D3 engineering staff, however they seemed to put a dozen handcuffs on them and forced incompatibility with their main lineup, something that runs against Nikon's brand reputation. I suspect that the failure of the consumer-oriented Nikon 1 coupled with the success of the full frame DSLRs and the eventual one-camera/lens success of the D3xxx (which as a single model outsold multiple Canon models) was one distraction. Nikon simply rode their horse too hard and long and it faded on the backstretch.

Canon wasn't particularly better at this, though they did put their toes into the more serious mirrorless waters earlier, at least at the bottom, crop-sensor end. Unlike Nikon, Canon didn't make the mistake of incompatibility.

So why did Olympus, Panasonic, and Sony all transition early to full mirrorless lineups? Look at the above matrix. They had small market shares, so how do you think you establish profitability against a duopoly? Play a different game (again, classic Reis and Trout strategy). And in playing a different game you get cost and manufacturing complexity benefits? What's not to like about that?

It was inevitable that the market for DSLRs would fade. Everyone saw that, some just acted on it earlier than others.

Most DSLRs made in the past decade are highly functioning products. Could I still do great work with a D800 (launched in 2012)? Absolutely. So getting DSLR owners to update/upgrade/iterate has become a tougher and tougher problem. Note that duality in my matrix: use benefits come with cost problems. The primary marketing issue for the camera makers has been and will continue to be that they need to somehow convince potential buyers/upgraders that the use benefits of mirrorless exceed the cost problems for a user. If they don't, no sale.

That's becoming more and more the DSLR problem: the D800 was a great camera, the D810 was a better camera, and the D850 was a still better camera, but the benefits have been getting tougher to market and the cost hasn't gone down, so sales tend to inevitably go down with each generation. Indeed, it's the D880 update problem in a nutshell: will Nikon change enough to show true user benefit over the previous models and justify customers paying the upgrade cost? (I can't answer that question other than in abstract. Nevertheless, I believe there's still enough lingering upgrade market in that category, as well as at the D500 level, to justify doing. Ironically, Nikon upgraded the D750, and there wasn't enough lingering upgrade market in that category as customers at that level were increasing shifting to mirrorless.)

Neither Canon nor Nikon has said much about their continued support of DSLRs. Canon did update two DSLRs in 2020 and two in 2019. Nikon updated one in 2020 and one in 2019.

The question that dedicated DSLR owners are all asking themselves is this: have we been abandoned? The matrix, above, would suggest that the camera makers would like to move on, as there are clear benefits to them that accrue by stopping making DSLRs and transitioning fully to mirrorless.

The only problem with that notion is that we've got over 200 million lenses out there that live best on the two primary DSLR mounts. While these can be used with adapters on the mirrorless models, that's not an optimal solution, just a pragmatic one.

What many serious users face when we consider the DSLR-to-mirrorless transition is this: during our transition we're likely to be half DSLR, half mirrorless, and that in itself poses issues. We keep our top DSLR as our backup body, use our DSLR lenses on our mirrorless camera to keep costs down short term. Not optimal.

It's becoming clear to me that there are three camps of DSLR users, and neither Canon nor Nikon is catering to any of them. Wow, talk about making your business problems bigger. What are the three camps?

- Dump the DSLR. One set of folk are dumping their DSLR and moving to mirrorless. They've determined the benefits of doing so are worth it and they have the disposable income, apparently, to do so. I have noticed that this group tends to be more one-camera, few lenses, though. If the DSLR makers were fully catering to this group you'd see far more DSLR-trade-in offers than we currently do.

- Straddle DSLR/mirrorless. This group is akin to what I used to call Samplers/Leakers, though their intention is now more determined. They're sticking their toes into the mirrorless waters because they've determined they're going to eventually go ahead and get completely wet, they just want to know on which beach. These folk tend to have more gear than Group #1, and they're reluctant to abandon it all at once because of the cost implications of having to replace everything. If the DSLR makers were really catering to this group, you'd see more transitioning offers (free adapters, mount conversions, complete-your-set bundle offers, and trade-ins).

- Keep the DSLR. Certainly at one level DSLRs and their lenses are so good that you could ride them right 'til they no longer work and can't be repaired. There's no real cost to the customer to do so, and they don't see a benefit that would trigger them to spend lots of money to transition to something they think is either the same or marginally better. If the DSLR makers were catering to this group, we would have seen (or soon see) a 5D Mark V, D580, and D880 with sensor stabilization, pixel-shift capability, on sensor phase detect for Live View/Video, and more.

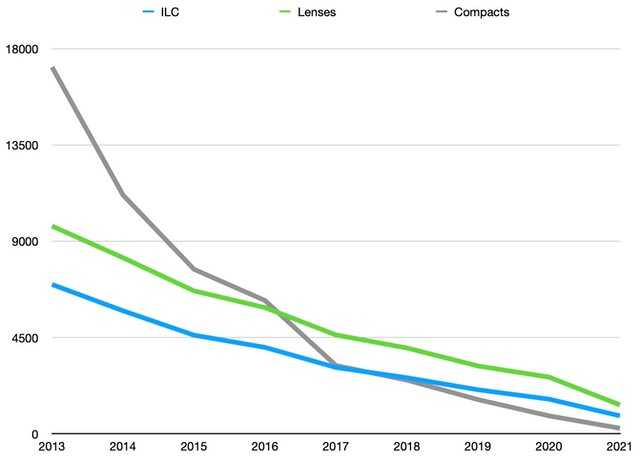

A lack of confidence also played into decision making in Tokyo, though. For example, Nikon's 2020 Annual Report says it right up front: "ongoing market shrinkage projected." Here's a graph derived from the fiscal year information Nikon has published (left axis is units, and note these are fiscal years, not calendar years):

Nikon also says "ongoing market shrinkage"? That means that they're making their bets based upon even lower overall unit volume. How low? My guess is 300k ILC units annually is the minimum Nikon would need to sell. I don't see Nikon (or anyone else) surviving profitability long-term below that level.

Nikon clearly sees that higher-end cameras and attracting upper-level users are necessary to survive on lower volume. That's because you need to sell at a high unit cost to get gross profit margin up high enough to cover fixed costs. Nikon keeps giving that lip-service in almost every executive pronouncement or financial report. And yet then we get a camera such as the Zfc, which is designed for casual use (those are Nikon's words, not mine). Where's the Z90 that competes with a higher-end Fujifilm X-T4?

The good news is that the next camera from Nikon is the Z9, which is most definitely going to be a display of everything they can do at the very highest end of interchangeable lens cameras. But I'd argue that we're a long way from seeing exactly how Nikon finally navigates the mirrorless transition. Nikon has too many gaps they need to still fill, and it's unclear how they'll fill them. So while we have some hindsight—Nikon transitioned late and didn't sustain the right DSLR models—we don't have complete hindsight yet.

Update: graph replaced and wording related to graph fixed accordingly.

The DSLR User's Greatest Fear

Petapixel recently had an article entitled "The Camera Industry is Trapped: Demand is There, But Products Aren't." The ongoing supply chain issues are creating quite a problem, from customer to dealer to camera maker.

But what wasn't said in that article is something that DSLR users are starting to fear. Basically, it boils down to this: with parts in short supply, the camera makers have to pick and choose which products they put them in. With Canon and Nikon both trying to transition to mirrorless and match up better against Sony's Alpha lineup, that means that critical parts are headed to mirrorless cameras, not DSLRs.

I suspect this problem has been around for a bit in different guises. The D500 and D850, for instance, have been in short supply for some time. We get small periodic batches of them hitting the shelves in the US, but they don't stay in stock for long. Indeed, B&H has started once again actively selling imported D500's, probably to make up for the lack of supply from NikonUSA.

Both the D500 and D850 use older versions of image sensors where the mirrorless cameras use newer ones. For example, the Z50 and Zfc use the same 20mp sensor base as the D500, but with enhancements. Thus, if Nikon has a fixed limit to the number of sensors they can get produced in a time frame and the combined Z50/Zfc/D500 volume exceeds that, guess which camera is going to get the short end of the stick?

This is one reason why I've been advocating for a D580 (and D880). By simplifying down to one image sensor as Nikon did with the Z6/Z6 II/D780, you have more flexibility to pick up some of those dedicated DSLR users who aren't going to switch to mirrorless any time soon. And I remind you (and Nikon): the D500, as it sits today over five years after being introduced, is still the best overall APS-C camera you can buy. Quality images, high performance, top focus system. Why would Nikon ever want to cede this Top Dog spot? Making a better D580 that holds the crown seems like a fairly trivial engineering exercise. The fact that it hasn't happened points to a strategic policy that dismisses the D500 over something that doesn't even exist in Nikon's mirrorless lineup.

Coupled with the on-going supply chain issue, that is what is now driving DSLR users' fear: that the current DSLR products are it. There's not enough parts to make new ones, and by forcing the issue of getting people to transition to mirrorless, Canon and Nikon are driving DSLR demand downward at the same time. At some point, this all becomes self-perpetuating.

It's not just cameras we're seeing dry up. EF and F-mount lenses are getting the same short shrift. Nikon recently cut production of the 70-300mm AF-P lens (it seems this might be temporary, but that's known for sure). Why? I suspect it's because it uses the same stepper motors that Nikon needs to deliver Z-mount lenses.

When DSLRs supplanted film cameras, that transition happened fast. Part of that was that DSLRs offered immediate review and didn't require constant media replacement. Customers caught on quite quickly to the advantages. Indeed, film SLR sales had not just peaked, but had dropped down to a lowish plateau in the decade prior to DSLRs appearing. DSLRs generated a whole new wave of buying, and DSLR sales quickly rose to far higher than film SLR sales.

The same thing isn't quite true of the DSLR to mirrorless transition. Not everyone sees clear advantages, and technically it's been eight years of (mostly) Sony trying very hard to get full frame mirrorless to DSLR levels, let alone above them. Moreover, what also doesn't get discussed much is the difference between consumer and prosumer/pro trajectories. Consumer DSLR has been in a nose dive, just like film SLRs made once DSLRs first came along. But the higher-end DSLR has not been in such a nose dive. Down some, yes, but I'd also argue that the camera makers themselves have been partially responsible for some of that downward trend. As in: today you can't buy a D500 off the shelf, so of course sales are down. Duh.

Another background point comes into play, as well: Canon and Nikon would rather stop making DSLRs. Why? Because the manufacturing process is so much more involved and costly. Sure, if we measured it dollars per unit we might still be in the single digits, but have you noticed that Nikon is saving less than pennies wherever they can (no hot shoe cover on the Zfc, for instance)?

So put all these things together and you get the great fear that dedicated DSLR users have: the camera makers are moving on, leaving the DSLR user behind. To put it into MBA-school terms: they've stopped milking the cow.

I really hope this isn't true. As you may recall, Nikon surprised the world with the F6 film SLR, which came after (and was based on) the D2h DSLR. For years this was not only the best film SLR you could buy, but it was about the only one. Clearly Nikon made not only money but brand reputation off that camera. I'd argue that they should do the same with a D580 and D880, and point to a DSLR road map that is solely D580, D880, and D6 as long as demand warrants. Last call on everything else, pointing to mirrorless for the rest of your needs.